“Sing that song from Germany,” my cousins would say to me over the phone when I was a little boy of four, newly arrived in Goa with my family from then West Germany in 1970. There would be peals of laughter at the other end when I complied.

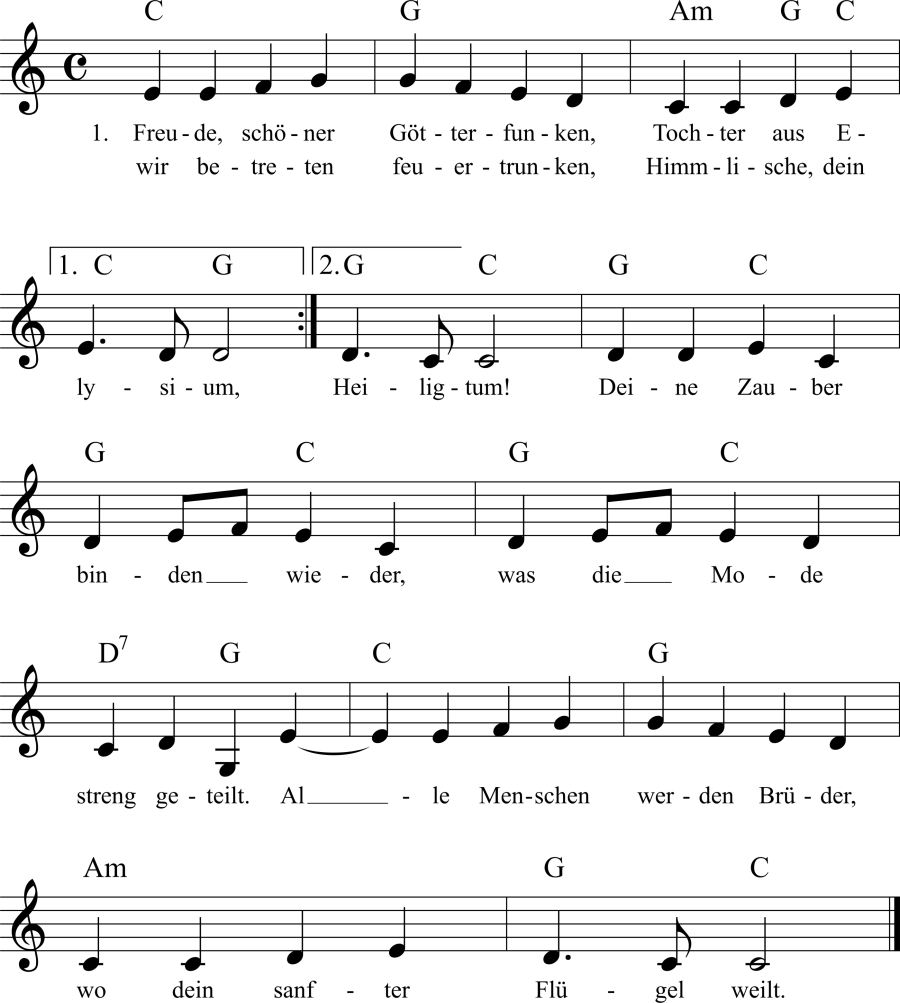

The “song” was the ‘Ode to Joy’ (‘An die Freude’ in the original German) from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony that our father taught his two sons.

We sang the lyrics by rote, with equal gusto as we did a kindergarten nursery rhyme, like ‘Alle meine Entchen’ (All my little ducklings).

So began my fascination with Beethoven’s crowning masterpiece that was first performed exactly 200 years ago, on 7 May 1824, a momentous milestone that I wrote about for the May issue ‘On Stage’ of Mumbai’s NCPA (National Centre for the Performing Arts).

What is it about Beethoven’s Ninth that gives it such universal, undiminished appeal?

In a 2020 Deutsche Welle documentary about it,

Greek conductor and founder of the orchestra MusicAeterna, Teodor Currentzis has an interesting perspective. To him, the symphony is not even about the words (the German poet Friedrich Schiller’s famous poem set to music by Beethoven) or the background story of Beethoven’s by-then complete deafness, poignant though it may be. “It is about defending humanity in front of God. [Beethoven] is the lawyer, the advocate of humanity.”

This to me is also why the melody of the famous verse is so deceptively simple (with the exception of one solitary note, its interval range is just a perfect fifth) that any child could sing it, as I could in my childhood. Beethoven deliberately wrote it to be universally singable by all humankind.

He was a great admirer of Schiller and had kept his 1785 ode ‘An die Freude’ (literally ‘To Joy’) in mind since the 1790s as possible grist to his creative mill. As early as 1808, he had also written an orchestral work that incorporated vocal soloists and mixed chorus (and piano) in his Choral Fantasy, Opus 80. So when he received a commission from London’s Philharmonic Society in December 1822, Beethoven now not only took this idea further but repurposed the melody from the 1808 work to set Schiller’s ode to friendship and brotherhood (adding some text of his own) in this symphony’s mammoth choral finale.

But the evolution was a gradual one. The Philharmonic Society commission was actually for two symphonies, and Beethoven’s ideas for the second were pretty strange:

He wrote: “Adagio cantique – pious song in a symphony in the ancient modes – Lord God, we praise thee – alleluia – either by itself alone or as introduction to a fugue. Perhaps the whole second symphony might be characterized in this way, whereby the vocal parts would enter in the last movement or already in the adagio. The orchestral violins are to be increased tenfold in the last movement. Or the adagio would be repeated in a certain way in the last movement, whereby the singing voices would enter one by one – in the adagio a text from Greek myth, a Cantique Ecclesiastique – in the allegro a celebration of Bacchus.”

The symphony as we know it today was premiered at Vienna’s Theater am Kärntnertor on Friday 7 May 1824 along with the overture ‘The Consecration of the House’ (Die Weihe des Hauses) and three parts of the Missa solemnis (the Kyrie, Credo, and Agnus Dei).

Despite being a Friday, when the nobility usually went to their country retreats for the weekend, the hall was packed with the city’s other prominent musicians that included Franz Schubert and Carl Czerny; and the Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich.

There are conflicting accounts of how the symphony was received. Some musicians found it too challenging despite more rehearsals than usual, and simply put down their instruments in the difficult segments. The orchestra had an able concertmaster in Beethoven’s longtime friend Ignaz Schuppanzigh, and the theatre’s Kapellmeister, Michael Umlauf as conductor.

Yet Beethoven stood by Umlauf’s side, and also conducted “like a madman” according to one orchestra violinist: “One moment he stretched to his full height, at the next he crouched down to the floor, he flailed about with his hands and feet as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the choral parts.”

After the Scherzo third movement, the contralto soloist, Caroline Unger had to gently turn the deaf composer to acknowledge wild applause and waving of handkerchiefs from the audience.

The gigantic scale, elemental power and originality of the work, however, bewildered both performers and listeners well into the nineteenth century before its current status as one of the world’s most frequently played symphonies.

There is a touching story attached to the massive fan following Beethoven’s Ninth (called ‘Daiku’, ‘Big Nine’) has in Japan.

Japan and Germany were on opposing sides in the First World War. In 1914, Japan captured 4000 German prisoners-of-war from Tsingtao, a city on the eastern shore of China, then a major German military base.

About 1,000 of those German soldiers were sent to Bando, a POW (prisoner-of-war) camp in Naruto, in Japan’s Tokushima Prefecture. To while away their time, the Germans took up several pursuits, among them music-making.

The 1918 performance by the “Bando orchestra” of Beethoven’s Ninth on a makeshift stage in the camp (transposing the women’s choral parts for men) was in effect the Japanese premiere of the work. After the war ended, the POWs returned to perform it again outside Bando’s walls for an audience in Naruto; in 1927.

It sparked a Japanese obsession for ‘Daiku’ that sees 10,000 singers gather in stadiums annually to give voice to Beethoven’s ‘advocacy’ in defence of humanity.

At the end of his New York Times op-ed to mark the Ninth bicentenary titled ‘What Beethoven’s Ninth Teaches Us’, pianist, conductor and humanitarian Daniel Barenboim wrote: “The Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci said a wonderful thing in 1929, when Benito Mussolini had Italy under his thumb. “My mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic,” he wrote to a friend from prison. I think he meant that as long as we are alive, we have hope. I try to take Gramsci’s words to heart still today, even if not always successfully.

By all accounts, Beethoven was courageous, and I find courage an essential quality for the understanding, let alone the performance, of the Ninth. One could paraphrase much of the work of Beethoven in the spirit of Gramsci by saying that suffering is inevitable, but the courage to overcome it renders life worth living.”

Is our time that much different? Like Gramsci, our minds may be pessimistic, but our will should continue to be optimistic.

One hears courage and optimism in equal measure in Beethoven’s Ninth, and that is what will ensure its eternal relevance to our human condition.

(An edited version of this article was published on 19 May 2024 in my weekend column ‘On the Upbeat’ in the Panorama section of the Navhind Times Goa India)