A year ago, I had written an article titled “How should we Listen?” in this Sunday column. I’d like to resume the discussion and build upon some ideas from there.

In this relatively ‘new’, 21st century, music is statistically more accessible and available to the public than it has ever been before. Looking back to the time of my own childhood, one couldn’t have dreamt of the portals available today: YouTube, Spotify, internet radio, and so many others that I haven’t even sampled yet. Just a few decades ago, this would have been outlandish, far-out science-fiction territory. But it is a reality that this generation takes for granted, as they perhaps should.

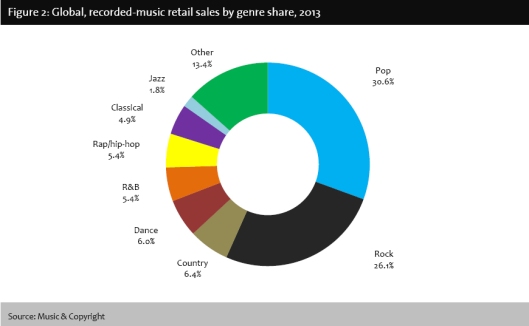

A 2013 survey of Global Recorded-Music Sales by Genre indicated that pop music accounted for 30.6%; rock 26.1%; and classical music a meager 4.9%; with “others” making up the remaining 38.4%.

Such statistics have been brandished time and again, as yet further proof of the moribund state of classical music. People have been sounding its death knell for at least the last two hundred years.

The British commentator (and author of the widely-read if often-controversial classical music blog ‘Slipped Disc’) Norman Lebrecht has in his writing, notably his 2007 book ‘Maestros, Masterpieces and Madness: The Secret Life and Shameful Death of the Classical Record Industry’, (marketed in the US under the title ‘The Life and Death of Classical Music’) lamented the decline and demise of the classical recording industry, if not of the genre itself, although his book expectedly raised hackles everywhere for different reasons.

But music education, especially for classical music, has been under attack for decades now, especially in the Western world, where one would imagine it to be nurtured the most; it is a soft target for cuts in funding whenever governments consider it necessary to do some financial belt-tightening.

Part of the problem with the failure to appreciate the importance of classical music is that we aren’t being taught how to listen well to it anymore, which contributes to the notion that it is “boring” or difficult to follow” or enjoy.

When I was a young child and began exploring my father’s bookshelf, one of the books that caught my attention was “William Shakespeare: The Complete Works”, which as you can imagine, was a weighty tome and difficult going for someone my age. But over time and keeping at it, I gradually began to unlock its secrets, and the process still continues. But the first time I cracked open the book’s spine, had I been daunted by the (then, to me) near-incomprehensible prose, the number of characters, the tangled plotlines, I would have been much the poorer for it, and a whole exciting world close off to me, merely for want of a sporting chance.

It is the same with classical music: one has to give it a chance, and repeated listening reaps huge rewards.

If one reads online forums devoted to music, and music listening comes up, often the well-intentioned advice is “Let the music just wash over you”, sometimes with the implied idea that the listener is passive in the process.

I submit that listening to classical music differs from many other genres of music in that to get its full benefit, one has to be an “active” listener. Be it a Mozart sonata, Beethoven symphony, Chopin waltz or even a Kreisler bonbon, one has to actively follow its musical “argument” and emotional “journey”, which is impossible to do if one is distracted and not giving it one’s fullest attention.

It is then that one better appreciates the beauty, the power and emotional intensity of the music. It helps us to become more intimately connected with the music, and it will stir emotions within us in ways that a cursory, distracted, “passive” way of listening to the same work never could.

In some ways, it is like reading a novel by a really good author. One has to follow the storyline, what happens to the protagonist(s), the villain(s) in the piece if any, but also the clever use of language, the painting of word-pictures, and so much more. The obvious difference of course is that one can put a bookmark in a book and take a break before returning back to it, whereas a piece of music needs to be listened from beginning to end. A possible exception could be the interval between Acts of an opera, or the gap of a few seconds between movements of a sonata, concerto or symphony, which are the equivalent of a ‘bookmark’, a pause before returning to the musical action.

Without meaning to denigrate pop music, which I love and enjoy as well, generally in pop music a much shorter attention span is necessary, with three-minute songs, with emphasis quite often on the lyrics and/or repetitive chord sequences and beats.

Listening to classical music is a different kind of experience which requires more “work” in comparison, but the rewards are huge. But active listening is an acquired habit that, like anything else, gets better and better with practice. It is this discipline of active listening which dictates much of the concert etiquette: maintaining silence so that you focus completely and do not disturb others who are doing the same. It is courtesy and respect for others in the audience as well, to say nothing of the performers and the music as well.

It is so easy to begin practicing “active listening”, with the wealth of choices, from CDs (with the additional advantage of so much information available on the booklet that often accompanies CDs, although today anything can be Googled as well) to MP3 to all the internet options as well. Over time, one may (or not) gravitate to ‘favourite’ performers, composers, or even recording eras. Getting used to a new style or ‘musical language’ requires repeated acquaintance through repeated listening before one is really familiar with it and how it works.

Although one doesn’t need state-of-the-art music equipment, listening through decent speakers or headphones and at a reasonable volume is important.

Coming back to giving classical music a chance: it applies to composers as well. There were composers I initially disliked, or whose music left me cold or unstirred, but over the years, with repeated listening and understanding more about their lives, the background to those works, and what motivated their writing in the first place, I have come to really love them and install them among the ever-growing pantheon of my demi-gods of music.

(An edited version of this article was published on 07 October 2018 in my weekend column ‘On the Upbeat’ in the Panorama section of the Navhind Times Goa India)