The obstruction to the Suez Canal by an ultra-large Golden-class container ship ‘Ever Given’ for just a week (23-29 March 2021) has highlighted just how vital the waterway is to global trade ever since its opening in 1869.

The vessel is one of the largest container ships in the world, at 400 meters in length almost as long as the Empire State building is tall, far exceeding the width of the Suez canal, under 300 meters at its widest, even in its 2015 newly-widened segment.

The Suez Canal has played its role in altering the course of history as well.

During the ‘Ever Given’ stalemate, I happened to watch an episode (Season 2, Episode 1) of the historical drama Netflix series ‘The Crown’,

aptly titled ‘The Misadventure’. It is a double entendre, referring both to Prince Philip’s extra-marital affairs as well as to Britain’s ill-advised involvement in the 1956 Suez crisis. This year 2021 marks its 65th anniversary.

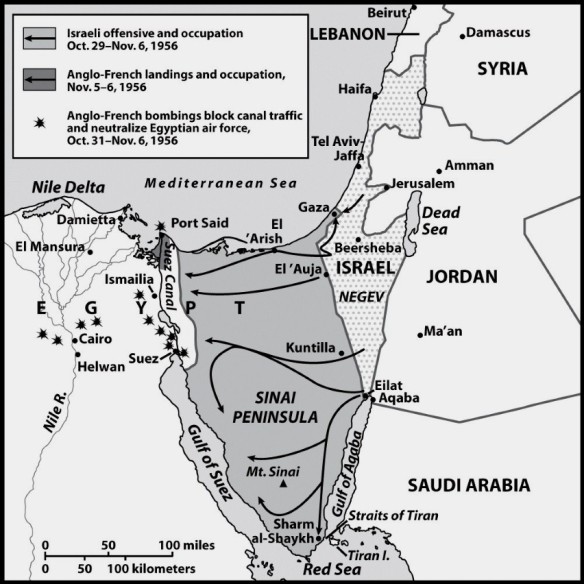

Briefly: Egypt’s nationalization of the Suez Canal by its fiery President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-1970)

was followed by the invasion of Egypt by Israel, joined later by Britain and France under the ostensible pretext of ‘peacekeeping’, but with the real intent of regaining control of the Canal. The Suez crisis is therefore called the second Arab-Israeli war or the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world.

The confrontation between Egypt and Britain put independent India and its first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964)

in a delicate position. All three nations belonged to the Commonwealth; but Nasser and Nehru (with Yugoslavia’s Josip Tito) were founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).

In fact, literally just a week before Nasser’s move to seize control of the Suez Canal, he had co-signed the Declaration of Brijuni in Yugoslavia on 19 July 1956, formalizing the birth of NAM.

Nasser had given no inkling to Nehru about what was obviously a calculated decision, bound to elicit a reaction.

The picture was complicated further by the United States romancing Pakistan in 1954; India thus felt compelled to maintain good relations with Britain as a sort of counterweight to this equation. India therefore had to tread cautiously.

Nehru wrote to C Rajagopalachari in August 1956: “This is by far the most difficult and dangerous situation in international affairs we have faced since independence…Probably we shall end by displeasing our friends on both sides.”

Shortly after Egypt’s takeover of the Suez Canal, an international conference comprised of the largest users of the Canal and a few other countries was held in London to defuse tensions. While Egypt refused to attend, it used India (and the Soviet Union) to represent its interests. Nehru (via the Indian delegate Krishna Menon) took India’s role of mediator seriously.

But the Tripartite Aggression by Israel, Britain and France a few months later caused Nehru to abandon the balancing act. Despite military successes by the three nations, pressure from the United States (enraged at having been kept in the dark about the military offensive by all three nations) and the Soviet Union threat of using nuclear weapons in Egypt’s defence led to a ceasefire. Egypt maintained sovereign control over the Suez Canal, and Britain and France lost what had remained of their post-WWII international clout. India was asked to lead the international United Nations peacekeeping force to enforce the armistice line between Egypt and Israel.

The role of Jawaharlal Nehru, both as leader of NAM and as India’s Prime Minister, was significant in this chapter in world history.

Nehru-bashing and airbrushing history have become almost a national pastime, but it is worth examining more closely his statesmanship, and hopefully, learning from it.

To quote Srinath Raghavan, senior fellow, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi (‘India should be prepared for the perils and prospects of diplomatic leadership’ Hindustan Times, 26 October 2016): “By showcasing its ability to play a genuinely independent role, India buttressed its standing as an Asian power. This history is worth recalling today. At a time when West Asia is in the throes of major conflicts, India is nowhere in the picture. It has stayed out of all international efforts to manage these conflicts, focusing instead on imminent threats to Indians living in the region. This stance sits awkwardly with India’s professed desire to be a leading power in its extended neighbourhood. The story of its involvement in the Suez crisis could offer New Delhi a lesson or two in the perils and prospects of diplomatic leadership.”

In what could be seen as Egypt’s ‘return of the favour’ to India, during the hostilities between India and Portugal leading up to the integration of Goa to the Indian Union in December 1961, an attempt by Portugal to send naval warships to Goa to reinforce its marine defences was foiled when President Nasser of Egypt denied the ships access to the Suez Canal.

It is interesting to note how it was reported in the international press. David Lawrence wrote in the Spokane Daily Chronicle on 23 December 1961 (‘Nasser Violates Pledge on Suez Canal Passage’), calling it “a grave blunder – possibly worse in its effects than Nehru’s theft of the Portuguese territory of Goa.” He speculated that “not long ago, Prime Minister Nehru stopped off at Cairo to visit President Nasser. Presumably an agreement was made then that if Portugal attempted to come to the rescue of her nationals in Goa, the Egyptians would block passage of any Portuguese ship through the Suez Canal. Such a deal would imply that the head of the Indian government disclosed his plans for aggression and Nasser was in effect, a party to them.”

It was followed by another short article: ‘Grab of Goa causes talk of Hong Kong, Macao’, the “alarm” over China possibly “taking the cue from India to invade the British colony of Hong Kong and the Portuguese colony of Macao.”

Egypt’s support of India over Goa in 1961 is also confirmed by Egyptian researcher Zaki Awad, El Sayed in ‘Egypt and India, A study of political and cultural relations, 1947–1964’, adding: “the fact that NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organisation] was supporting the Portuguese military action did not deter Egypt from standing by India.”

As it transpired, neither the NATO alliance nor the centuries-old Anglo-Portuguese treaty (“to be friends to friends and enemies to enemies”) worked to Portugal’s advantage in this instance.

My guess is that even if Nasser had allowed the Portuguese warships through the Suez, the conflict might have been longer-drawn and bloodier, but it wouldn’t have changed the outcome.

Be that as it may, one couldn’t fail to register the irony when reading this excerpt in Charles Hallberg’s book ‘The Suez Canal: Its History and Diplomatic Importance’. The same waterway that “brought back to the Mediterranean the traffic in oriental commodities which, ever since the epochal voyage of Vasco da Gama late in the fifteenth century, had followed the long route around the Cape of Good Hope” by the very act of its blockage of access played its part in 1961 in facilitating Portugal’s exit from its most-cherished and longest-held possession, beginning just 12 years following that 1498 ‘epochal’ voyage.

(An edited version of this article was published on 11 April 2021 in my weekend column ‘On the Upbeat’ in the Panorama section of the Navhind Times Goa India)